Behavioral science has taught us that humans are “predictably irrational.” For example: we fear losses more than we value gains. We stick with defaults. We follow the herd. These insights have shaped everything from retirement savings programs to organ donation policies. But there's a problem with this story. It assumes neurotypicality.

The Problem with "Normal"

It is now widely recognized that most behavioral research is built on WEIRD samples, which stands for populations that are Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (Henrich et al., 2010). But there's another assumption buried even deeper: that participants possess "standard" patterns of attention, sensory processing, executive function, and social cognition. In other words, that they're neurotypical.

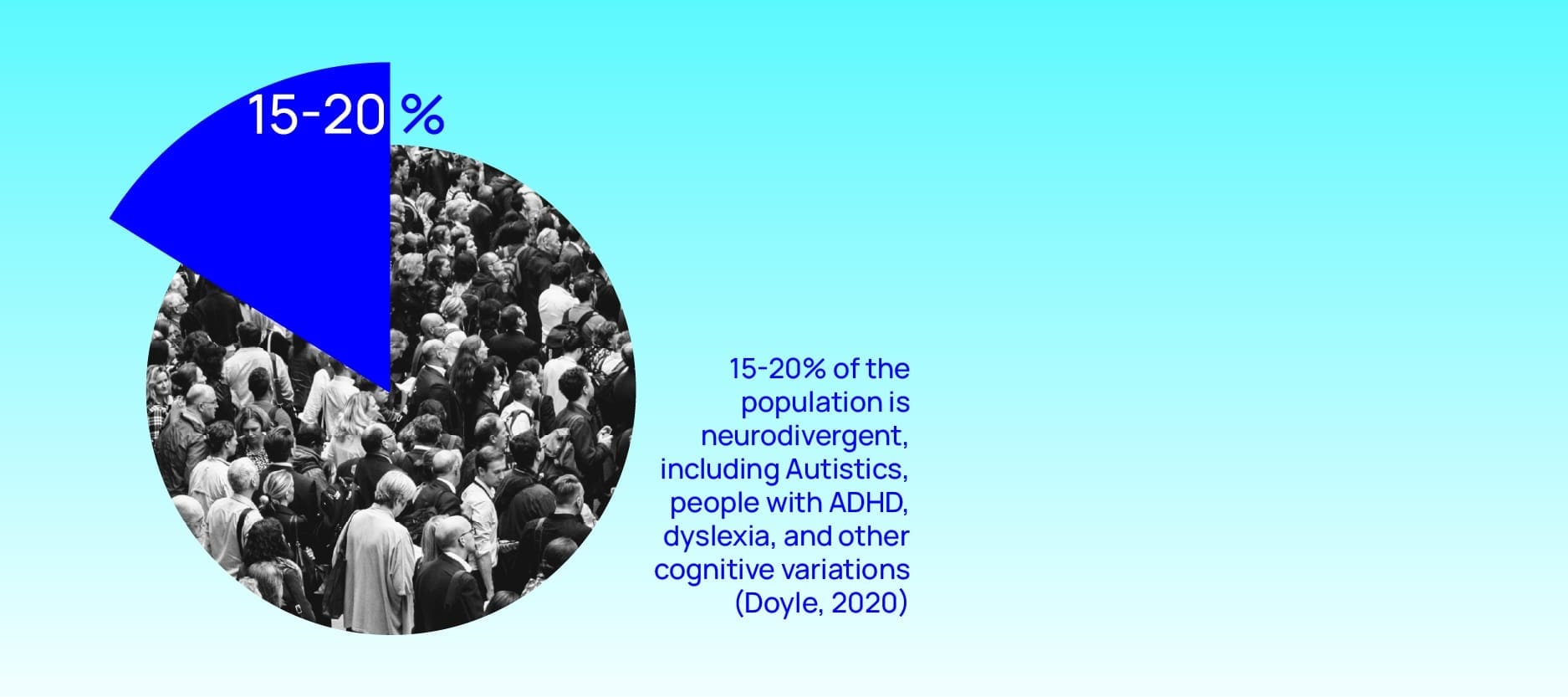

This assumption warrants attention because approximately 15-20% of the population is neurodivergent, including Autistics, people with ADHD, dyslexia, and other cognitive variations (Doyle, 2020). When behavioral models fail to account for this diversity, we don't just exclude people. We miss crucial information about how our interventions actually work, and for whom.

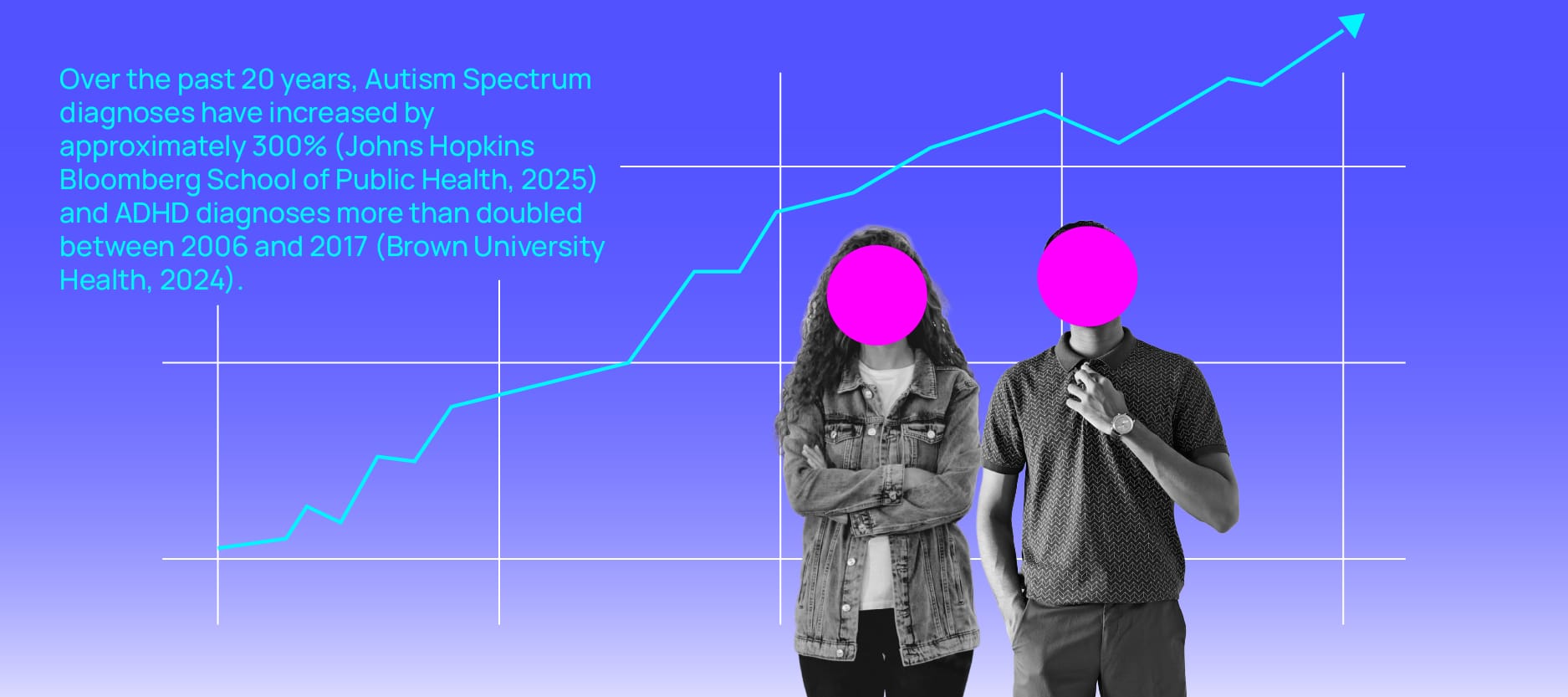

It is also important to be aware that the proportion of the population identified as neurodivergent is exponentially increasing. Over the past 20 years, Autism Spectrum diagnoses have increased by approximately 300% (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2025) and ADHD diagnoses more than doubled between 2006 and 2017 (Brown University Health, 2024). These increases are due to greater awareness of their symptoms and increased screening, as well as broadened definitions. This trend is on track to continue, reinforcing that there is no such thing as “normal.” Therefore, designing for neurodiversity will become less about “edge cases” and more about acknowledging the simple fact that there is a broad variation of processing styles across humanity.

A Different Order, Not a Disorder

Neurodiversity advocate Frankie Abralind uses the term "difforder" to describe neurodivergence: not a disorder, but a different order (Abralind, 2024). It's a small linguistic shift that carries profound implications.

Autism is a spectrum that encompasses diverse traits, strengths, and challenges varying significantly from person to person (Jaarsma & Welin, 2012). ADHD manifests differently across contexts and individuals. Highly Sensitive People (HSPs) experience intensified responses to sensory and emotional stimuli that shape how they navigate the world (Aron, 1997).

Applied to neurodivergence, this means cognitive differences become "disorders" primarily when environments are optimized for only one neurotype.

These aren't flaws. They're variations in how human minds work.

The social model of disability makes this distinction clear: impairment is individual limitation, while disability emerges from social barriers that convert difference into disadvantage (Oliver, 1990, 1996). Applied to neurodivergence, this means cognitive differences become "disorders" primarily when environments are optimized for only one neurotype.

This is where behavioral science comes in. Our field has long recognized that when desired behaviors fail to occur, the solution is environmental modification, not blaming individuals (Skinner, 1953). When people don't save for retirement, we design better choice architectures. When software users get confused, we create clearer interfaces.

Yet we often fail to extend this principle to neurodivergence. When Autistic individuals struggle in open-plan offices, we pathologize their sensory sensitivities rather than question the design of the space.

What’s In It For Us?

Here's where it gets interesting for behavioral science practitioners: neurodivergent individuals reveal important boundary conditions for our behavioral principles.

Take loss aversion, one of the most robust findings in behavioral economics. People typically fear losses more than they value equivalent gains (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). But for many individuals with ADHD, immediate gains can outweigh the fear of future losses, especially when long-term consequences feel abstract (Patros et al., 2016; Sonuga-Barke, 2003).

This isn't irrationality. It's a different weighting of temporal and probabilistic information, linked to the same cognitive profile that enables the valuable divergent thinking and creativity many ADHDers exhibit (White & Shah, 2006).

This suggests many of our behavioral principles about social influence may actually describe neurotypical-to-neurotypical interaction rather than universal dynamics.

Default bias is another cornerstone principle. Most people accept preset options, which is why automatic enrollment dramatically increases retirement savings participation (Johnson & Goldstein, 2003).

But Autistic individuals may respond differently. Research suggests they're less susceptible to social influence and framing effects (Shah et al., 2016), alongside strong preferences for predictability and personal control (Pellicano & Burr, 2012). A default that conflicts with established routines may be actively resisted rather than passively accepted.

This isn't rigidity. It reflects different trade-offs between autonomy, consistency, and conformity.

The double empathy problem adds another layer. Autism researcher Damian Milton (2012) challenged the traditional view that Autistic people lack empathy. Instead, he proposed that empathy difficulties are bidirectional – neurotypical and Autistic individuals struggle equally to understand each other, but only Autistic people get pathologized for this mutual misunderstanding.

Recent studies support this. Information transfer occurs just as effectively in Autistic-Autistic dyads as in neurotypical-neurotypical dyads, but it breaks down in mixed pairs (Crompton et al., 2020). This suggests that many of our behavioral principles concerning social influence may, in fact, describe neurotypical-to-neurotypical interaction rather than universal dynamics.

Sentinel Signals: Learning from the Edges

The authors of this article propose that our field reframes neurodivergent responses not as noise to be filtered out, but as sentinel signals – early warnings that reveal where our models have blind spots and our interventions reach their limits.

This concept has precedent. In design thinking, "extreme users" – people with unusual needs – are deliberately studied because they reveal problems typical users have learned to work around (Kelley, 2001; Brown, 2009). The design-thinking company IDEO made this a core methodology.

Neurodivergent individuals are the “extreme users” of our behavioral interventions, organizational systems, and social environments. But their heightened sensitivity to environmental features, explicit processing where others rely on automaticity, and resistance to suboptimal defaults aren't bugs. They are features that expose weaknesses in our designs.

Consider what this looks like in practice:

- When standard data-exclusion practices systematically remove participants with high response time variability or who fail attention checks, we may be inadvertently excluding neurodivergent individuals whose cognitive patterns diverge from neurotypical norms (Siritzky et al., 2023). These so-called "quality control" measures can introduce what researchers term "shadow biases" – sample distortions that go unreported and unacknowledged.

- When neurodivergent participants engage in "masking" (suppressing their natural responses to appear more neurotypical), what we measure is not authentic behavior but masked behavior (Hull et al., 2017). This doesn't just compromises individual well-being; it compromise our data.

- When interventions designed on neurotypical samples are deployed broadly, we may be optimizing for a specific cognitive (read: neurotypical) profile rather than human behavior writ large.

The Curb-Cut Effect: Designing for Everyone

This awareness represents an exciting opportunity: accommodations designed for neurodivergent needs often improve outcomes for people across the board.

This parallels the "curb-cut effect" in accessibility design (Blackwell, 2017). The Americans with Disabilities Act’s 1990 mandate of curb cuts to facilitate sidewalk access for wheelchair users ended up also helping parents with strollers, delivery workers, elderly pedestrians, and travelers with luggage, to name a few. Designing for inclusivity improved usability for everyone.

The same pattern appears in behavioral interventions:

SMS medication reminders were initially developed for ADHD patients struggling with consistency due to working memory challenges. When deployed broadly, these reminders improved medication adherence by 10-25% across diverse populations (Kannisto et al., 2014; Thakkar et al., 2016). The intervention addressed a universal challenge – remembering daily tasks amid competing demands – but was discovered by attending to an amplified version of the challenge for people with ADHD.

Sensory-sensitive design motivated by Autistic individuals' documented sensory processing differences has shown broader benefits. Hospital lighting redesigns found that softer, adjustable lighting reduced patient pain medication requests, shortened stays, and improved staff satisfaction (Ulrich et al., 2008). While the changes were initially motivated by responding to hypersensitivity in some patients, they ultimately addressed universal human reactions to harsh institutional environments.

Because neurodivergent individuals experience these challenges at a higher level of intensity, they are quicker to generate demand for solutions.

Workplace noise reduction is increasingly recognized as a valuable accommodation for Autistic employees and those with sensory processing sensitivity. It improves concentration, reduces stress, and increases productivity across a diverse population of workers (Evans & Johnson, 2000).

Plain language and clear structure – accommodations commonly requested by Autistic individuals and those with learning disabilities – reduce errors and misunderstandings for everyone, including non-native speakers and people experiencing heavy cognitive load (Cutts, 2020).

Why this pattern? Neurodivergent experiences often represent amplification rather than deviation. Attention varies continuously across the population; ADHD sits at one end of the spectrum. Sensory sensitivity also exists on a spectrum; Autistic individuals and HSPs experience heightened versions of it. Executive function capacity varies widely; neurodivergent individuals may experience lower capacity or higher demands on that capacity depending on their environmental conditions.

A noisy airport lobby that's merely distracting for neurotypical individuals may be completely overwhelming for Autistic people. A complicated automobile registration form that's annoying for most drivers can become genuinely insurmountable for someone with dyslexia.

Because neurodivergent individuals experience these challenges at a higher level of intensity, they are quicker to generate demand for solutions. Once developed, these solutions benefit broader populations by addressing the same challenges at lower intensity.

What This Means for Practice

If you're a behavioral science practitioner, here is what this framework suggests for your work:

1. Test your interventions across cognitive diversity, and make it visible.

Don't assume that what works for neurotypical populations will work universally. When piloting interventions, explicitly recruit across the spectrum of cognitive variation. When you find differential effectiveness, that's valuable information about boundary conditions.

Our vision is that, in the future, the definition of a “representative research sample” should expand to consistently include a range of cognitive processing profiles. Just as we report the demographic characteristics of our samples, we should also measure and disclose cognitive diversity. Validated screening tools are already available for assessing Autistic traits (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001), ADHD symptoms (Kessler et al., 2005), and sensory processing sensitivity (Aron & Aron, 1997).

2. Reconsider your exclusion criteria.

Are your data quality standards systematically filtering out neurodivergent responses? Before excluding participants with "unusual" response patterns, consider whether you're removing valuable signals about intervention limitations.

3. Welcome neurodivergent stakeholders in design.

Participatory design that welcomes neurodivergent individuals as co-designers, not just research subjects, can identify usability issues and innovation opportunities early (Spiel et al., 2019). Their insights often reveal latent problems in the broader population.

4. Design for adjustability.

Rather than seeking a single optimal default, create interventions with customization options. Adjustable sensory environments, flexible communication formats, and alternative interface designs enable people to optimize for their specific needs. This isn't inefficiency – it's acknowledging that one size doesn't fit all.

5. Question your assumptions

When proposing behavioral principles, explicitly consider how each principle holds up across cognitive diversity. Does this principle assume certain attentional capacities? Does it rely on automatic social processing? Making these assumptions explicit enables more precise and inclusive application.

The Real-World Implications

Our call to consider neurodiversity in behavioral science isn't just an academic technicality. It has immediate, and important, practical consequences.

- In healthcare: Are your medication adherence interventions leveraging loss aversion? Consider that they may work differently for patients with ADHD. Could you reframe them or incorporate immediate rewards instead?

- In product design: Does your interface rely on default acceptance? Consider that Autistic users may need explicit reasons to trust your defaults or clear paths to customize.

- In workplace design: Are you optimizing for "average" sensory preferences? Consider that sensitivity-friendly modifications like adjustable lighting, quiet spaces, and fragrance-free policies improve well-being and productivity broadly.

- In communications: Are you assuming neurotypical social processing? Consider that explicit, structured communication with written confirmation benefits many people beyond Autistic individuals who specifically request it.

- In research: Are your sample composition and exclusion practices inadvertently creating neurotypical-only findings? Consider how your conclusions might change with more inclusive sampling.

Challenges and Nuances

This paradigm shift isn't without complications.

Neurodivergence is heterogeneous. Autism alone encompasses individuals with vastly different support needs and experiences (Mottron, 2011). We must avoid treating "neurodivergent" as a homogeneous category when designing interventions.

Some accommodations involve trade-offs. Detailed written instructions help some neurodivergent individuals while potentially creating information overload for others. Quiet environments benefit sensory-sensitive individuals but may feel isolating to those who work better with more stimulation.

This makes the case for flexible, customizable systems rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

We acknowledge that there are practical constraints on our recommendations. Measuring cognitive diversity adds participant burden. Deliberate sampling increases costs. Validating measures across diverse populations demands resources.

The good news is that we practitioners have already proven ourselves capable of similar change: these challenges parallel those we've increasingly accepted regarding cultural diversity and demographic representation. The question now is whether, and when, our community of behavioral scientists & designers decides that cognitive inclusion merits similar priority.

From Correction to Co-Creation

Accommodate neurodivergence not out of charity, but because it leads to better design, stronger outcomes, and richer innovation

The way forward is two-fold:

Celebrate neurodiversity for the creativity, insight, and systemic awareness it brings. Recognize neurodivergent people not as broken or burdensome, but as valuable informants about where our models fall short. Welcome them to express themselves openly on our teams.

Accommodate neurodivergence not out of charity, but because it leads to better design, stronger outcomes, and richer innovation. Accommodations aren't special treatment – they're universal design principles in disguise.

Too often, neurodivergent behaviors are treated as anomalies to filter out. But what if they're exactly the signal we need to redesign our environments, workflows, and systems?

Neurodivergent individuals frequently notice flaws before others do. By designing with their insights in mind, we don't just include them – we deepen our innovation. We build systems that work better for everyone. We become more perceptive, ethical, and effective practitioners.

Behavioral science aims to understand human behavior and improve the systems we live in. But to truly do this, we must expand our frameworks to include a broader spectrum of neurotypes.

Inclusion isn't just a moral imperative – it's a methodological upgrade.

If we want smarter interventions, more ethical nudges, and more humane design, we must design with outliers in mind. Because outliers aren't a problem to solve. They're partners in building what comes next.

Recommended further reading:

Rose, N. (2021). Nobody’s normal: How culture created the stigma of mental illness. W. W. Norton & Company.

References

Abralind, F. (2024). Difforder. Retrieved from https://www.frankieabralind.com/post/difforder

Aron, E. N. (1997). The highly sensitive person: How to thrive when the world overwhelms you. Broadway Books.

Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1997). Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(2), 345-368.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5-17.

Blackwell, A. G. (2017). The curb-cut effect. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 15(1), 28-33.

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. HarperBusiness.

Brown University Health. (2024, October 15). ADHD: Why is diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder rising? Brown University Health.

https://www.brownhealth.org/be-well/adhd-why-diagnosis-attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-rising

Crompton, C. J., Ropar, D., Evans-Williams, C. V., Flynn, E. G., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). Autistic peer-to-peer information transfer is highly effective. Autism, 24(7), 1704-1712.

Cutts, M. (2020). Oxford guide to plain English (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Doyle, N. (2020). Neurodiversity at work: A biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults. British Medical Bulletin, 135(1), 108-125.

Evans, G. W., & Johnson, D. (2000). Stress and open-office noise. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 779-783.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83.

Hull, L., Mandy, W., Lai, M. C., Baron-Cohen, S., Allison, C., Smith, P., & Petrides, K. V. (2017). Development and validation of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(3), 819-833.

Jaarsma, P., & Welin, S. (2012). Autism as a natural human variation: Reflections on the claims of the neurodiversity movement. Health Care Analysis, 20(1), 20-30.

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. (2025). Is there an autism epidemic? Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2025/is-there-an-autism-epidemic

Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338-1339.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

Kannisto, K. A., Koivunen, M. H., & Välimäki, M. A. (2014). Use of mobile phone text message reminders in health care services. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(10), e222.

Kelley, T. (2001). The art of innovation: Lessons in creativity from IDEO, America's leading design firm. Currency.

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E., ... & Walters, E. E. (2005). The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS). Psychological Medicine, 35(2), 245-256.

Milton, D. E. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The 'double empathy problem'. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883-887.

Mottron, L. (2011). Changing perceptions: The power of autism. Nature, 479(7371), 33-35. Oliver, M. (1990). The politics of disablement: A sociological approach. Macmillan. Oliver, M. (1996). Understanding disability: From theory to practice. Macmillan.

Patros, C. H., Alderson, R. M., Kasper, L. J., Tarle, S. J., Lea, S. E., & Hudec, K. L. (2016). Choice-impulsivity in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 161-173.

Pellicano, E., & Burr, D. (2012). When the world becomes 'too real': A Bayesian explanation of autistic perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(10), 504-510.

Shah, P., Catmur, C., & Bird, G. (2016). Emotional decision-making in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(4), 1362-1371.

Siritzky, E. M., Cox, P. H., Nadler, S. M., Grady, J. N., Kravitz, D. J., & Mitroff, S. R. (2023). Standard experimental paradigm designs and data exclusion practices in cognitive psychology can inadvertently introduce systematic "shadow" biases in participant samples. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 8(1), 66.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2003). The dual pathway model of AD/HD: An elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 27(7), 593-604.

Spiel, K., Brulé, E., Frauenberger, C., Bailly, G., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2019). Micro-ethics for participatory design with marginalised children. Proceedings of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 1001-1012.

Thakkar, J., Kurup, R., Laba, T. L., Santo, K., Thiagalingam, A., Rodgers, A., ... & Chow, C. K. (2016). Mobile telephone text messaging for medication adherence in chronic disease. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(3), 340-349.

Ulrich, R. S., Zimring, C., Zhu, X., DuBose, J., Seo, H. B., Choi, Y. S., ... & Joseph, A. (2008). A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 1(3), 61-125.

White, H. A., & Shah, P. (2006). Uninhibited imaginations: Creativity in adults with ADHD. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1121-1131.