The Centre for Social and Behaviour Change at Ashoka University is uniquely positioned to liaise with the central and state governments of India, the largest scale-up organizations in the world, for operationalizing evidence-based behavioral interventions.

Even with rigorous causal evidence in their favor, we’ve seen interventions fail to translate into a program or a set of job responsibilities that the supply side of policy can easily deliver. In this article, we delve into the behavioral barriers that impede last-mile scale-up in India, specifically:

- There is a job responsibility overload that does not align with frontline policy implementers’ expectations. The same implementer is expected to deliver multiple interventions to a variety of beneficiaries, and transitions between job responsibilities lack streamlining.

- An effective incentive structure for implementers is not in place. They are not paid a sufficient salary that would increase extrinsic job motivation, and there may not exist the appropriate institutional mechanisms to sustain intrinsic motivation.

- The onus of filling the gaps in translating how interventions were delivered by trained professionals during an RCT and how they will be delivered at scale falls upon untrained frontline implementers, who are left to make an educated guess as to what they need to do.

We will subsequently recommend the following applications of behavioral science to change the behavior of supply-side agents:

- When we work on scaling an intervention, we must acknowledge that we are trying to break a routine and install a new one. Incorporating implementers’ learning and habit-changing costs into intervention testing could have a significant impact on their scalability.

- Behavioral diagnostic research is required to understand the incentives that are currently driving implementers’ job motivation, and whether there are better rewards to consider. For instance, the opportunity for upward mobility and job security through public sector jobs is an important incentive. We describe an intervention designed and tested by CSBC to increase job motivation (and subsequently job performance) of frontline policy implementers in Bihar, India.

- Interventions must be bootstrapped down to a set of clear, concise instructions for implementers to follow. The cognitive load of translating interventions to programs needs to be reduced. We elaborate on CSBC’s scalability-testing phase with a case study of interventions designed to increase iron and folic acid supplementation in India.

Psychological Contract Breach and Job Responsibility Overload Among Frontline Policy Implementers

The behavior of public policy implementers in India is well-encapsulated through the lens of psychological contract breach and cognitive dissonance (Rousseau, 1998). When signing up for a policy implementer’s job, an individual carries preconceived and established beliefs about the reciprocal obligations, rights, and benefits the job entails. These beliefs form the implementer’s psychological contract (PC) with their implementation orga-

nization (including, but not limited to, the local government).

The PC of a typical policy implementer in India would include the following core beliefs:

- Stipulated working hours, tasks, and effort expectations

- Expectations of a safe income and post-retirement pension

- Expectations of respect and privilege from their network and beneficiaries

Formed in the initial few months of their job, this PC serves as a mental model for the implementer to frame their behavior within and even outside of their job. The individual and organizational factors shaping the PC of a typical policy implementer in India would include:

- Individual factors: Predispositions about the aspirational nature of governmental jobs, reference points for upward mobility set by peers or role models in their network, and one’s personal prosociality-based motivation to work for the public good. We discuss below how policy implementers’ motivation is threatened and suggest interventions to address this problem.

- Organizational factors: Initial information shared by employers, coworkers, and supervisors that could lack clarity regarding the socialization and promotion process. In Abdel-All et al., 2019, policy implementers express a pre-established preference for the possibility of career progression and training leading to promotion, along with fixed incentives. As we will discuss later, these expectations are not met.

Importantly, when an individual faces discrepancies in their expectations and the actual state of affairs, they may make adjustments to their beliefs and behavior. This relates to Festinger’s (1962) cognitive dissonance theory. Robinson (1996) argues that “flexible, dynamic, and changing modern work environments increase the probability of psychological contract breach”. A government-dependent job would easily fulfill these criteria. Local governments routinely change. So do politicians, bureaucrats, and the policies that they must prioritize and implement. Perceived contract breach (PCB) can occur when the policy implementer is arbitrarily asked to halt their routine of delivering policy A, learn a new set of implementation guidelines for policy B, and start delivering it. Or they may be asked to stack the implementation of policy B on policy A for the same beneficiaries. In both these cases, from the implementer’s perspective, PCB occurs, as their employer has failed to adequately fulfill their obligations of having pre-decided tasks and effort expectations. Unless empathetic steps were taken to facilitate this transition by the supervisor, the hassle and cognitive load of

breaking old routines to learn new ones add to the PCB. Let us consider the example of one of India’s key types of frontline policy implementers, the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA). ASHAs are women who belong to the same community where they deliver policy benefits, making the role an essential last-mile link between governments and citizens. An ASHA’s PC would include the implementation of various health programs across various villages, with multiple health indicators they must improve (for example, immunization rates, maternal mortality, and infant mortality).

In the absence of organizational commitment and trust, policy implementers may express high intention to leave, and job performance may worsen.

As per the National Rural Health Mission’s guidelines, ASHAs are technically volunteers who choose to help deliver policy benefits, primarily driven by intrinsic motivation. Being an ASHA is supposed to be a part-time, unpaid supplement to an individual’s primary livelihood. The time commitment outlined as an initial obligation is two to three hours daily for four days a week. These components are key components of an individual’s PC when signing up for the role of an ASHA.

However, various studies have documented ASHAs working for considerably longer hours than stipulated in the PC, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Khandre et al., 2022; Bajpai & Dholakia, 2011). Additional pandemic duties were offloaded to ASHAs, constituting a PCB in terms of the tasks they must perform. Kawade et al. (2021) qualitative inquiry with ASHAs in the Pune district of Maharashtra revealed that 58 out of 67 ASHAs in their sample had been tasked with at least 10 additional responsibilities (including conducting surveys and facilitating financial inclusion by asking people to open bank accounts, the latter notably is not related to health policy). The authors note a prevalent willingness to take up these additional tasks in their sample which relates to the importance of prosocial motivation we discuss in the next section.

An ASHA stated they demanded extra compensation for new workloads, arguably to justify their additional effort through extrinsic motivation, since prosocial motivation may be a limited resource. ASHAs clearly and repeatedly demand higher financial incentives for their work and claim that they would put in greater effort, even work full-time, in return for commensurate compensation.[1]

The consequences of PCB that signal the breach occurred and has affected job performance are clear in studies of ASHAs’ job performance. Post-pandemic, many instances of ASHAs going on strike across states to demand higher pay, regularization of work, and social protection were covered by the national news (Ambast, 2021). In the absence of organizational commitment and trust, policy implementers may express high intention to leave, and job performance may worsen.

Su-Fen Chiu and Jei-Chen Peng (2008) effectively sum up the literature on the effect of PCB on job performance—employees exhibit dissatisfaction with their job, frustration, and anger, discretionary absenteeism (Deery, Iverson, & Walsh, 2006), and job neglect (Lo & Aryee, 2003). Mondal and Murhekar (2018) found quantitatively that ASHAs in the Howrah district of West Bengal with relatively lower job performance scores were more likely to serve a larger population than that stipulated in their job role (1,200), or they were lacking supervisory support from ANMs.

In the context of policy implementers, these negative job behaviors imply enormous operational costs for governments, loss of working days because of absenteeism, and greater churn among implementers.

Gautam Patel, CSBC’s Policy Lead at the NITI Behavioral Insights Unit (BIU), the Uttar Pradesh BIU, and the Bihar BIU, quotes an educational intervention that was intended to be scaled through governmental institutions/schools as a case study in job responsibility overload affecting scalability. An educational intervention to improve student learning of two specific subjects was tested with non-governmental teachers who were dedicated to testing the intervention. The intervention, which was proven effective in the non-governmental context, struggled to float within governmental institutions, primarily because of their myriad distractions. Government school teachers were roped into national and state-level campaigns and missions such as the Swachh Bharat Abhiyaan and elections-related activities. Their non-teaching-related work rendered the scaling of a straightforward two-hour teaching intervention difficult.

When a non-governmental organization conducts an evaluation, we see impact, but that impact often fails to replicate when piloted by government staff. Governments setting up dedicated workforces to implement specific policies may not be the best answer either. In CSBC’s experience, despite a government agreeing to set up a new dedicated workforce for a policy’s implementation, it was impossible to prevent the new staff from being pulled into other work. This systemic inclination to be distracted could be addressed through “campaign-mode” or “drive-mode” phases—short bursts of time wherein staff is dedicated to a singular high-priority task.

Job Motivation and Performance

In a motivational assessment administered with various types of community health workers, including ASHAs, in the Ambala district of Haryana, low levels of job motivation were correlated with job burnout, job insecurity, lack of career progression opportunities, and poor supervisory support (Tripathy et al., 2016).

To maintain prosocial motivation, implementers need regular positive feedback from others.

What are the factors that motivate frontline policy implementers? We considered two key elements:

-

Extrinsic motivation: We reference Deci and Ryan’s (2004) self-determination theory, whereby employees engage in their work to achieve a goal that is distinct from the inherent satisfaction of the work. We focus on the extrinsic motivation that is externally regulated; i.e. behavior driven by external rewards and punishments. Some of these rewards are embedded in the implementers’ PC—the possibility of career progression and promotion, job security, and fixed monetary incentives.

- Along with the earlier reference to the demands of ASHAs for promotions and increments (Tripathy et al., 2016), through an experimental approach, Abdel-All et al. (2019) observed that the possibility of promotions is an important factor driving employee motivation in Community Health Work (CHW). Over 85% of the participating ASHAs were willing to switch to a CHW job with the prospect of career progression that offered them a monthly salary that was Rs. 2,530 less than a job without career progression.

- Therefore, implementers currently operate in a working environment that lacks satisfactory extrinsic motivators.

- The Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) is an example of how extrinsic incentive structures could improve implementers’ job performance. JSY introduced a set of financial incentives for mothers and community health workers to promote prenatal care, institutional childbirth, and postnatal care. ASHAs receive 250 Rupees for transporting a woman to a medical center for delivery, and another 150 Rupees immediately after the delivery. Another 200 Rupees is given to the ASHA after the newborn receives the appropriate immunizations within two weeks of delivery (MoHFW, n.d.). There is no separate incentive for ensuring adequate postnatal care for the mother. ASHAs receive the post-delivery incentive of 400 Rupees regardless of whether they had scheduled antenatal care visits. ASHAs receive the post-delivery incentive in cash immediately at the hospital itself, while availing the postnatal care incentive requires the ASHA to track the beneficiary down again and schedule a visit.

- Therefore, ASHAs may prefer to not bother with postnatal care visits and focus instead on maximizing their institutional deliveries. This behavioral pathway explains Joshi’s (2014) observation—while the rate of institutional deliveries has increased post-JSY, prenatal and postnatal care rates remain largely unchanged. Behaviorally auditing extrinsic incentive structures and re-aligning them to better influence behavior can therefore prevent such behavioral fallout.

-

Intrinsic and prosocial motivation: Both these types of motivation are relevant to understanding frontline policy implementers’ behavior in the absence of adequate extrinsic motivation.

- Intrinsic motivation comes from within, and implementers enjoy their work for its own sake. Prosocial motivation requires conscious effort and self-control. To maintain prosocial motivation, implementers need regular positive feedback from others.

- Khandre et al. (2022) confirm this motivational pathway by observing that positive feedback from beneficiaries helped induce a sense of responsibility within ASHAs to work further for the public good. However, the lack of positive feedback from both beneficiaries and supervisors led to a decline in their job satisfaction, indicating the strength of the pro-social motivation component. In particular, some ASHAs reported a non-supportive dynamic with supervisors; for instance, there was supervisory pressure to complete policy targets along with the hassle of navigating sludge in getting documents signed by supervisors to complete their work.

- When intrinsically motivated, employees are process focused—they see the work as an end in and of itself (Amabile, 1993). When prosocially motivated, employees are outcome focused—they see the work as a means to the end goal of benefiting others (Grant, 2008).

- Kawade et al. (2021) find that ASHAs derived self-esteem through their work, and even use that sentiment to offset the inadequate financial compensation. ASHAs carefully observe when and how their community health work moves indicators—one agent reported pride in having encouraged more women to opt for institutional deliveries (Kawade et al., 2021).

How do we ensure policy implementers remain motivated, especially when career progression and other extrinsically-motivating incentive structures are inadequate? Building on the employee motivation literature (Dowling & Sayles, 1978, p. 16) (Latham & Pinder, 2005) (Amabile, 1993), in 2022, we tested the efficacy of Facebook group-based job training modules for public policy implementers working under the Government of Bihar’s Rural Livelihoods Promotion Society (JEEViKA).

We tested whether fostering dialogue across hierarchies of cadres, including work-related discussions and problem-solving, increases their intrinsic and prosocial motivation to deliver policy benefits, and subsequently leads to an increase in job performance. We posited that a Facebook-based peer group would heighten JEEViKA cadres’ positive feedback with each other and to their work, while simultaneously delivering training modules that improve their competence. Results show a positive and small though statistically insignificant effect.

In its work with JEEViKA, CSBC has also observed how crisis periods strongly influence and sustain prosocial motivation and behavior. Immediately after the devastating “Delta variant wave” of COVID-19 in India, JEEViKA cadres overcame the hesitation of working during the pandemic in favor of saving their community through immunization efforts.

Making Interventions Scalable for Existing Policy Delivery Infrastructure

Who delivers the intervention when implementing RCTs? Trained enumerators, paid more than policy implementers, bringing an entirely distinct PC to their work, as compared to typical policy implementers. To step closer to a “perfect” imitation of the policy during the testing phase as it would perform during the scale-up phase, it is imperative that we somehow replicate the PC of policy implementers within the experiment, along with other barriers such as potential cognitive load and dissonance brought on by the cost of learning how to deliver

the new policy.

We usually intend for our interventions to act as job aids with minimal invasiveness on an implementer’s routine.

Involving intervention designers and prototyping teams in the experiment design stage may induce a shift in how we create interventions as well, by taking cognizance of how they will be tested, and whether their appearance during the tests will closely reflect their scale-up version or not.

There are three questions to consider in determining which interventions can be made “more scalable” for implementation:

- How can we replicate the PC of policy implementers within enumerators?

- How can we design the intervention to minimize the likelihood of PCB among policy implementers?

- Is it necessary to have a different evaluation—a scalability test—that specifically measures how easy it is for the policy implementers at the grassroots level to deliver the intervention we designed?

At CSBC, we involve bureaucrats, policy implementers, and other non-governmental scale-up organizations during stakeholder workshops wherein the interventions are designed. The prototypes we develop are empathetic of the implementer PC, and we usually intend for our interventions to act as job aids with minimal invasiveness on an implementer’s routine so that implementers simply carry the CSBC-designed job aid along with them during their routine work.

Since 2018, CSBC has been working on tackling anemia among pregnant women by enhancing the consumption of iron and folic acid tablets. Through extensive diagnostic research and behaviorally-informed prototyping, we designed two job aids intended for incorporation into the routine tasks of ANMs (Auxiliary Nurse Midwives) and ASHAs. Anemia is highly prevalent among pregnant women in India.[2] Strengthening iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation is imperative fr preventing and treating anemia (WHO, 2012). IFA pills are distributed under the Anemia Mukt Bharat (AMB) policy led by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of the central Indian government, but only 26% of pregnant women consume IFA tablets for the recommended number of days (NFHS-5, 2019-20). IFA supplementation is evidently a demand-side problem in India. CSBC’s behavioral audit identified various behavioral barriers preventing pregnant women from routinely consuming IFA tablets, two of the primary ones being:

- Barrier A: Lack of adherence—The side effects of IFA tablets were deterring pregnant women from consuming them.

- Barrier B: Intangible payoffs of consuming the tablets—The benefits of consuming IFA tablets were not clear, leading to their de-prioritization.

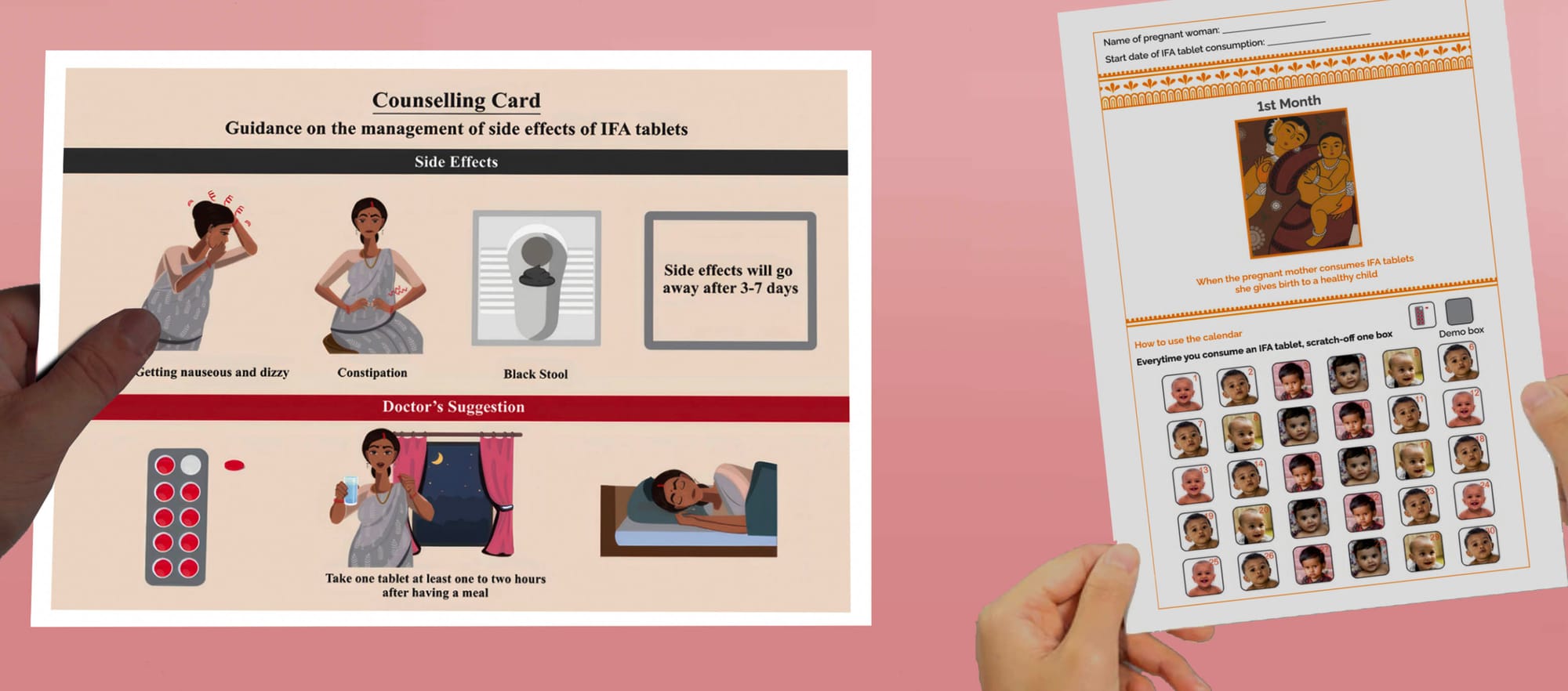

To tackle barrier A, CSBC designed a counseling card that made salient the actual side effects of consuming IFA tablets and how to deal with them (see image 1). This card was intended as a job aid to be carried by ANMs and ASHAs during their counseling sessions with pregnant women.

Counseling card and goal-tracking calendar developed by CSBC

For barrier B, CSBC designed a goal-tracking calendar that provides the user with a reminder to consume the tablets while making salient the benefits of consuming them (by demonstrating the visual progress of happy children) (see image 1).

We subsequently conducted an RCT with a sample of 1,200 pregnant women to test the efficacy of these interventions in increasing IFA tablet consumption. Both interventions were successful to increase the adherence to IFA tablets, as compared to the control group.

Our key “scalability” arguments are relevant here, in the post-RCT and pre-scaling-up phase. For this purpose, CSBC undertook a three-pronged approach to understand the most efficient way to integrate these interventions in the existing health-policy machinery of Anemia Mukt Bharat (AMB) at the grassroots level, without disturbing pre-existing dynamics. We:

- Behaviorally audited existing policy documents on the distribution of IFA tablets, counseling, and anemia-related IEC materials under AMB.

- Consulted with Frontline Health Workers (ANMs and ASHAs), pregnant women, and block and district-level officials to understand the existing processes under the AMB strategy.

- Consulted with relevant stakeholders in NITI Aayog, the Department of Public Health and Family Welfare, and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare to validate the findings of the policy review and qualitative study and refine the operational guidelines.

These consultations formed the first phase of the evaluation of these interventions’ scalability. We conducted a non-experimental, observational evaluation of the interventions’ performance in the scale-up phase by asking ANMs to deploy them during their routine counseling sessions and observing their performance in health centers. Feedback was subsequently collected from the ANMs and incorporated into our scale-up framework for efficient integration of the interventions in existing delivery platforms.

The scalability evaluation phase resulted in two sets of operational guidelines being drafted to recommend implementation mechanisms for the counseling card and the goal-tracking calendar. These operational guidelines provided clear and concise steps for the relevant central, state, district, and village-level officials to follow to deliver these interventions through their existing health-policy delivery infrastructure. The concerns we have elaborated on in the previous sections—policy implementers’ PCB, cognitive load, and cost of breaking routines—were empathetically incorporated into these operational guidelines.

The guidelines suggest modifiable and non-modifiable features for the design and delivery of the interventions. This allows implementers to make context-specific changes while retaining

the behavioral features of the interventions, given India’s extensive social and cultural diversity. The guidelines include a short and interactive training guide that may be integrated into the existing anemia-related training materials to prevent policy implementers from being cognitively overloaded by new tasks.

To prevent the costs and hassle of breaking existing routines, the guidelines suggest roles and responsibilities for stakeholders at various stages, including estimation, printing, storage, delivery, training, implementation, and monitoring. Finally, to ensure the intervention iterates upon itself, the guidelines suggest the Responsive Feedback approach, which involves taking regular feedback from grassroots policy implementers to make continuous and timely improvements to the interventions and their delivery.

Conclusion & Key Points

The authors posit that applying behavioral science insights to understand frontline policy implementers’ job systems and adapting policy interventions to their idiosyncrasies can improve scalability in the Global South. Policy interventions that are transformational in their implementation plan, those that do not seamlessly integrate into existing policy implementation infrastructure, are bound to induce psychological contract breaches within implementers. This can lower job satisfaction and performance. Before systemic changes that deal with PCB can be implemented, such as better onboarding processes, regular job expectations evaluations and goal-setting exercises, and conscious efforts by supervisors to minimize job responsibility overload, interventions must be designed with the intention to

minimize PCB.

CSBC shows how to design such an intervention during its work on IFA supplementation in India. Thorough behavioral audits to understand how to seamlessly fit interventions into

existing routines, designing simple interventions that reduce cognitive load, and engaging with diverse stakeholders during the scalability research process are imperative to ensuring the success of large-scale policy interventions. New scalability-specific research must be conducted with implementers to observe how well the intervention performs, with an emphasis on novel measures of hassle aversion, cognitive load, and willingness to implement.

Finally, we observe that certain policies have extrinsic incentive structures that disproportionately favor specific components of a policy by influencing implementers’ behavior. To address the larger systemic barriers and facilitators of extrinsic, intrinsic, and prosocial motivation, thorough behavioral audits must be conducted to trace how existing incentive structures influence policy implementation. New policy interventions should attempt to regularly update their incentive structures according to the progress of the interventions’ outcome indicators.

References

- Abdel-All, M., Angell, B., Jan, S., Howell, M., Howard, K., Abimbola, S., & Joshi, R. (2019). What do community health workers want? Findings of a discrete choice experiment among Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) in India. BMJ Global Health, 4(3), e001509.

- Ambast, S. (2021). Why do ASHA workers in India earn so little?. Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability.

- Amabile, T. M. (1993). Motivational synergy: Toward new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review, 3, 185-201.

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D.A. (1992). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bajpai, N., & Dholakia, R.H. (2011). Improving the performance of accredited social health activists in India. Mumbai: Columbia Global Centres South Asia.

- Batson, C.D. (1998). Altruism and prosocial behavior. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 282–316). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Chiu, S.F., & Peng, J.C. (2008). The relationship between psych logical contract breach and employee deviance: The moderating role of hostile attributional style. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 426-433.

- Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of self-determination research. University Rochester Press.

- Deery, S.J., Iverson, R.D., & Walsh, J.T. (2006). Toward a better understanding of psychological contract breach: a study of customer service employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 166.

- Dowling, W.F., & Sayles, L.R. (1978). How managers motivate: The imperatives of supervision. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford University Press.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E.L. (2005). Self‐determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331-362.

- Grant, A.M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 48.

- Joshi, S., & Sivaram, A. (2014). Does it pay to deliver? An evaluation of India’s safe motherhood program. World Development, 64, 434-447.

- Kawade, A., Gore, M., Lele, P., Chavan, U., Pinnock, H., Smith, P., et al. (2021). Interplaying role of healthcare activist and home-maker: a mixed-methods exploration of the workload of community health workers (Accredited Social Health Activists) in India. Human Resources for Health, 19, 1-12.

- Khandre, R.R., Jakasania, A., & Raut, A. (2022). “We are working for seven days a week”: Time motion study of accredited social health activists from central India. Medical Journal Armed Forces India.

- Kehr, H.M. (2004). Integrating implicit motives, explicit motives, and perceived abilities: The compensatory model of work motivation and volition. Academy of Management Review, 29, 479–499.

- Latham, G.P., & Pinder, C.C. (2005). Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 495–516.

- Lo, S., & Aryee, S. (2003). Psychological contract breach in a Chinese context: An integrative approach. Journal of Management Studies, 40(4), 1005-1020.

- MoHFW (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare). (n.d.). Features and Frequently Asked Questions and Answers: Janani Suraksha Yojana. Maternal Health Division, MoHFW, Government of India. https://nhm.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/97827133331523438951.pdf.

- Mondal, N., & Murhekar, M. V. (2018). Factors associated with low performance of accredited social health activist (ASHA) regarding maternal care in Howrah district, West Bengal, 2015–‘16: an unmatched case control study. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 6(1), 21-28.

- Morrison, E.W., & Milliken, F.J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706-725.

- NFHS-5. (2019-20). National Family Health Survey, India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

- Rai, R.K., & Singh, P.K. (2012). Janani Suraksha Yojana: the conditional cash transfer scheme to reduce maternal mortality in India–a need for reassessment. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 1(4), 362.

- Ryan, R.M., & Connell, J.P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749.

- Tripathy, J. P., Goel, S., & Kumar, A. (2016). Measuring and understanding motivation among community health workers in rural health facilities in India-a mixed method study. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 1-10.

- Robinson, S.L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 574-599.

- Rousseau, D. M. (1998). The ‘problem’ of the psychological contract considered. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 665-671.

- Quinn, R.W. (2005). Flow in knowledge work: High performance experience in the design of national security technology. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50, 610–641.

- Wang, Y.D., and Hsieh, H.H. (2014). Employees’ reactions to psychological contract breach: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(1), 57-66.

- WHO. (2012). Daily iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnant women. Geneva: World Health Organization, 27.

In Tripathy et al. (2016), a majority of the sample reported having worked as a community health worker for several years without being promoted. Cases of more experienced health workers earning roughly the same as those who started the job recently were prevalent. An ANM reported that they had no appropriate authority for voicing these concerns. ↩︎

About 52% of pregnant women in India are anemic (NFHS-5, 2019-20). ↩︎